Dashboard

The Global Forecast System (GFS) - Global Spectral Model (GSM)

(Updated May 2016, March 2018, June 2019, and March 2021)- Recent GFS implementation details

- Post processor:

- Variables:

- Operational output variables created by post (starting page 17)

PLEASE NOTE : The following documentation is for the Global Spectral Model, which ran in the GFS from 1980-2019. For documentation on the current GFS, click on the "Documentation" link at the top of the dashboard on the left side of this page.

1.0 The NCEP Global Forecast System (GFS)

The NCEP's Global Forecast System (GFS) is the cornerstone of NCEP's operational production suite of numerical guidance. NCEP's global forecasts provide deterministic and probabilistic guidance out to 16 days. The GFS provides initial and/or boundary conditions for NCEP's other models for regional, ocean and wave prediction systems. The Global Data Assimilation System (GDAS) uses maximum amounts of satellite and conventional observations from global sources and generates initial conditions for the global forecasts. The global data assimilation and forecasts are made four times daily at 0000, 0600, 1200 and 1800 UTC.

1.1 Forecast model

The atmospheric forecast model used in the GFS is a global spectral model (GSM) with spherical harmonic basis functions. In response to increased computing resources and changing computer architecture at NCEP, the GFS has evolved to higher resolution, both horizontally and vertically, and a more modular code structure. The current operational horizontal resolution is T1534 (T574), or approximately 13 km (34km) at the equator for days 0-10 (days 10-16) forecasts. In the vertical there are 64 hybrid sigma-pressure (Sela, 2009) layers with the top layer centered around 0.27 hPa (approximately 55 km). The current operational dynamical core of the GFS/GSM is based on a two time-level semi-implicit semi-Lagrangian discretization (Sela, 2010) with three dimensional Hermite interpolation (the dynamical core still supports three time-level Eulerian approach). The semi-Lagrangian advection calculations as well as treatment of physics are done on a linear, reduced (for computational economy) Gaussian grid in the horizontal domain. The semi-implicit treatment and implicit eighth order horizontal diffusion are performed in spectral space. This requires the application of Fourier and Legendre transforms to convert between spectral and grid-point spaces. To improve the accuracy of associated Legendre function computation at higher wave numbers, an extended-range arithmetic (X-number - Juang, 2014) is used. To reduce noise in the stratosphere, additional second order divergence damping that increases with altitude is applied above ~100hPa. Also, a correction is applied to the global mean ozone to account for the non-conservation during semi-Lagrangian advection step.

For the three time-level Eulerian option for dynamics a positive-definite tracer transport formulation (Yang et al., 2009) is used in the vertical.

It is important to note that the same physical parameterization package is used across all horizontal and vertical resolutions (with slightly different tunable parameters). Upgrades to the physical parameterizations are ongoing and occur on the average of every other year.

1.2 Changes to physical parameterization since 2007 include:

1.2.1 Radiation:

The longwave (LW) and the shortwave (SW) radiation parameterizations in NCEP's operational GFS are both modified and optimized versions of the Rapid Radiative Transfer Models (RRTMG_LW v2.3 and RRTMG_SW v2.3, respectively) developed at AER Inc. (Mlawer et al. 1997, Iacono et al., 2000, Clough et al., 2005). The LW algorithm contains 140 unevenly distributed g-points in 16 broad spectral bands, while the SW algorithm includes 112 g-points in 14 bands. In addition to the major atmospheric absorbing gases of ozone, water vapor, and carbon dioxide, the algorithm also includes various minor absorbing species such as methane, nitrous oxide, oxygen, and up to four types of halocarbons (CFCs). To mitigate the unresolved sub-grid cloud variability when dealing multi layered clouds, a Monte-Carlo Independent Column Approximation (McICA) method is used in the RRTMG radiation transfer computations. A maximum-random cloud overlapping method is used in both LW and SW radiation calculations. Cloud condensate path and effective radius for water and ice are used for calculation of cloud-radiative properties. Hu and Stamnes' method (1993) is used to treat water clouds in both LW and SW parameterizations. For ice clouds, Fu's parameterizations (1996, 1998) are used in the SW and LW, respectively.

In the operational GFS, a climatological tropospheric aerosol with a 5-degree horizontal resolution is used in both LW and SW radiations. A generalized spectral mapping formulation was developed to compute radiative properties of various aerosol components for each of the radiation spectral bands. A separate stratospheric volcanic aerosol parameterization was added that is capable of handling volcanic events. In SW, a new table of incoming solar constants is derived covering time period of 1850-2019 (Vandendool, personal communication). An eleven-year solar cycle approximation will be used for time out of the window period in long term climate simulations. The SW albedo parameterization uses surface vegetation type based seasonal climatology similar to that described in the NCEP Office Note 441 (Hou et. al, 2002) but with a modification in the treatment of solar zenith angle dependency over snow-free land surface (Yang et al. 2008). Similarly, vegetation type based non-black-body surface emissivity is used for the LW radiation. Concentrations of atmospheric greenhouse gases are either obtained from global network measurements, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), or taking the climatological constants, such as methane, nitrous oxide, oxygen, and CFCs, etc. In the operational GFS, the actual CO2 value for the forecast time is an estimation based on the most recent five-year observations. In the lower atmosphere (< 3km) a monthly mean CO2 distribution in 15 degree horizontal resolution is used, while a global mean monthly value is used in the upper atmosphere.

1.2.2 Boundary layer:

To improve daytime planetary boundary layer (PBL) growth, a hybrid eddy-diffusivity mass-flux (EDMF) PBL parameterization has been developed and implemented into the NCEP GFS as of January 2015, where the EDMF parameterization is applied only for the strongly unstable PBL, while the old GFS eddy-diffusivity counter-gradient parameterization is used for the weakly unstable PBL. For the vertical momentum mixing, the mass-flux parameterization is modified to include the effect of the updraft-induced pressure gradient force. Along with the hybrid EDMF parameterization, the heating by turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) dissipation is parameterized to reduce an energy imbalance in the GFS. To enhance a too weak vertical turbulent mixing for the weakly and moderately stable conditions, on the other hand, the current local parameterization in the stable boundary layer is modified to use an eddy-diffusivity profile method.

1.2.3 Gravity wave drag and mountain blocking:

The gravity wave drag and mountain blocking parameterizations are modified to automatically scale with model resolution. Compared to the T382L64 version of GFS, the T574L64 version uses four times stronger mountain blocking and one half the strength of gravity wave drag. The orographic gravity wave drag and mountain blocking parameterixation is scale aware in the GFS and implemented across NCEP global and regional models alike following the work of Alpert et al., (1988, 1996) and Kim and Arakawa (1995). Mountain blocking is incorporated from the Lott and Miller (1997)Recent GFS implementation details parameterization with minor changes, including their dividing streamline concept. A parameterization of stationary convectively forced gravity wave drag proposed by Chun and Baik (1998) and tested in GCMs by Chun et al. (2001, 2004) was implemented in the T1534 (13km) GFS in Jan 15, 2015, following Ake Johansson (2008) and the work of the GCWMB staff. Modest positive effects from using the parameterization are seen in the tropical upper troposphere and lower stratosphere.

1.2.4 Shallow convection:

A new mass flux shallow convection parameterization is developed based on the bulk mass-flux parameterization of deep convection. Separation of deep and shallow convection is determined by cloud depth (currently 150 hPa). Entrainment rate is given to be inversely proportional to height and much larger than that in the deep convection parameterization. Mass flux at cloud base is given as a function of the surface buoyancy flux.

1.2.5 Deep convection:

The Simplified Arakawa-Schubert (SAS) deep convection parameterization is revised to make cumulus convection stronger and deeper to reduce excessive grid-scale precipitation. Random cloud-top selection is replaced by an entrainment rate approach with an environmental moisture dependent entrainment rate. Convective overshooting and the effects of convection-induced pressure gradient force (which reduces convective momentum transport) are included. The cloud condensate is detrained from upper cloud layers above downdraft initiating level.

1.2.6 The Noah Land Surface Model (LSM):

In early 2005 the land surface model (LSM) of GFS was upgraded from two soil layer (10, 190 cm thick) Oregon State University model to four soil layer (10, 30, 60, 100 cm thick) Noah model. The Noah LSM includes addition of frozen soil physics, new formulations for infiltration and runoff (giving more runoff for unsaturated soils), revised physics of the snowpack and its influence on surface heat flux and albedo, tuning and addition of canopy resistance parameters, spatially varying root depth, revised treatment of ground heat flux and soil thermal conductivity, reformulation for dependence of direct surface evaporation on first layer soil moisture, and improved seasonality of green vegetation cover. The frozen soil physics includes soil heat sinks/sources from freezing/thawing and influences vertical transport of soil moisture, soil thermal conductivity and heat capacity, and surface infiltration. The prognostic states of snowpack depth and liquid soil moisture were added to the already present prognostic states of snowpack water-equivalent (SWE), total soil moisture (liquid plus frozen), soil temperature, canopy water, and skin temperature. SWE divided by the snowpack depth gives the snowpack density. Total soil moisture minus liquid soil moisture gives the frozen soil moisture.

The addition of Noah LSM greatly reduced the two prominent biases in land-surface processes: 1) an early depletion of snowpack; and 2) a high bias in both surface evaporation and precipitation in the warm season in non-arid mid-latitudes. However, a lower tropospheric warm bias as well as increased surface sensible heat flux emerged, particularly over the arid areas during the daytime. Extensive tests attributed this bias mainly to improper treatment of the thermal roughness length. In May 2011, a new thermal roughness length formulation, which assigned a smaller value for the thermal roughness length compared to the momentum roughness length, was implemented. This greatly reduced the warm surface air temperature bias and the cold skin temperature bias over the arid areas during the daytime.

In January 2015, CFS/GLDAS soil moisture climatology at T574 was used for soil moisture nudge to replace the out-of-date coarse resolution bucket soil moisture climatology; a dependence of the ratio of the thermal and momentum roughness on vegetation type was added to address the land-atmosphere coupling strength; a look-up table based on vegetation type was used to replace 1.0 degree momentum roughness length climatology. After this implementation summer warm/dry biases were found over cropland/grassland areas. Some evaporation-related parameters were refined to increase the evaporation to address this issue. The refinement was implemented in May 2016.

1.3 The Global Data Assimilation System (GDAS):

The initial conditions for the global forecasts are obtained through the Global Data Assimilation System (GDAS). The GDAS ingests all available global satellite, conventional (rawinsonde, aircraft, surface) and radar observations with a plus or minus 3:00 hour window of the analysis time. A 9-hour GSM forecast (T1534 interpolated to T574) from the previous GDAS analysis is used as the first guess for the assimilation. The GDAS runs with a late (6:00) data cutoff to provide the next 6 hourly cycle background using the largest amount of available observations.

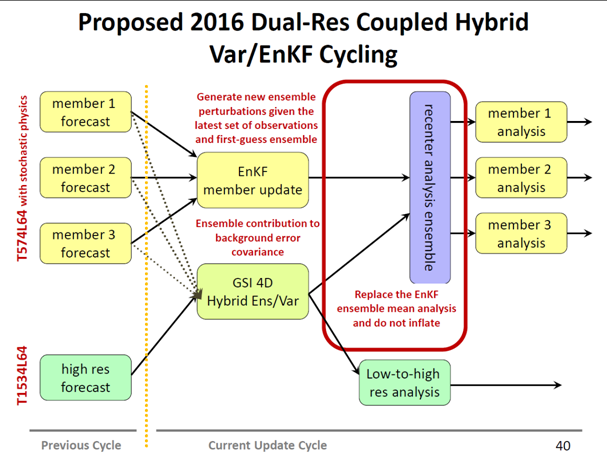

The GDAS uses a hybrid four-dimensional ensemble variational formulation (Hybrid 4DEnVar, Buehner et al. 2013). In this formulation, the propagation of the background error covariances in time is approximated by an hourly ensemble of forecasts (Figure 1.1), rather than by a tangent linear and adjoint model as in 4DVar formulations. The 4DEnVar method is more scalable and computationally inexpensive with respect to 4DVar and is also more easily applied to other models. Within a variational framework, the hourly ensemble covariances are combined with a time-invariant estimate of the background error derived from the model's 24-48 hour forecast climatology. The ensemble covariance comprises 87.5% of the total background error covariance while the climatology portion comprises 12.5%. Additional changes to the analysis formulation include a reduction of the horizontal localization length scales in the troposphere as well as the inclusion of multivariate ozone covariances.

Figure 1.1: A schematic of the dual-resolution hybrid 4DEnVar assimilation system that became operational in May 2016.

Due to the inclusion of hourly background covariances, it is now possible to extract time information from a portion of the observations. 4D thinning has been applied to the atmospheric motion vectors and the time component of the data selection procedure for all observations has been removed, no longer giving preference to observations at the center of the observing window. Another major recent addition to the GDAS is the implementation of a variational bias correction for the aircraft temperature data, reducing the warm bias in the upper troposphere. Also, the GDAS is now able to assimilate AMSU-A microwave radiances that are affect by non-precipitating clouds. The Community Radiative Transfer Model (CRTM) has also been updated to better process these cloudy radiances.

1.4 The post processing system:

The GFS replaced its post processing system with NCEP Unified Post Processor in 2007. Using a common post processor for all NCEP weather models allows NCEP to compare and verify all model output fairly. The NCEP Unified Post Processor computes most variables in the same way as previous GFS post processor. The largest difference is that the NCEP Unified Post does not filter its output.

GFS post processing system continues to add new variables with each GFS upgrades. These new variables include simulated GOES, membrane sea level pressure, fire weather variables, and new global aviation products.

GFS started to distribute higher resolution 0.25 degree data to users with its 2015 upgrade. GFS began distributing hourly 0.25 degree data up to F120 in May 2016. Several new variables will also be added, including five layers of stratospheric state fields and global In Flight Icing severity.

1.5 July 2017 upgrade and transition to FV3 Dynamic Core

The last upgrade to the Global Spectral Model in the GFS was implemented in July 2017 which included the following changes :

1) Changes to the Global Forecast System Global Spectral Model (GSM) components:

- Implement GSM source code in NOAA Environmental Modeling System (NEMS) framework.

- Replace spectral history file output (sigma files) with new nemsio binary files on model native grid. Documentation of nemsio format including data structure, interface, how to open, read, write, and MPI I/O support are at https://www.emc.ncep.noaa.gov/emc/pages/infrastructure/nems.php and nemsio library at http://www.nco.ncep.noaa.gov/pmb/codes/nwprod/lib/nemsio.

- Implement Near Surface Sea Temperature (NSST) to replace Real-Time Global SST (RTGSST) to provide more realistic ocean boundary conditions.

- Upgrade deep and shallow convection schemes with scale- and aerosol-aware features along with convective cloudiness enhancement.

- Modify Rayleigh damping to improve temperature and wind forecasts in the upper stratosphere.

- Upgrade the land surface model to increase ground heat flux under deep snow; and unify snow cover fraction and snow albedo.

- Use new high-resolution MODIS-based snow-free albedo, maximum snow albedo, soil type and vegetation type.

- Upgrade surface layer parameterization scheme to modify the roughness-length formulation and introduce a stability parameter constraint in the Monin-Obukhov similarity theory to prevent the land-atmosphere system from decoupling.

2) Changes to the Global Data Assimilation System (GDAS) and Tropical Storm Relocation:

- Upgrade GDAS and Ensemble Kalman filter (EnKF) to use nemsio binary files.

- Implement Near Sea-Surface Temperature (NSST) Analysis.

- Implement CrIS full resolution data assimilation capability.

- Implement readiness for new Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES-16), Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS-2) and Constellation Observing System for Meteorology, Ionosphere and Climate (COSMIC-2) data assimilation capability.

- Extend Regional Advanced Television Infrared Observation Satellite (TIROS) Operational Vertical Sounder (ATOVS) Retransmission Services (RARS) and Direct Broadcast Network (DBNet) capability.

- Implement bug fix to cloud water increment in Gridpoint Statistical Interpolation (GSI).

- Upgrade land surface type specification in Community Radiative Transfer Model (CRTM).

- Update data monitoring for Megha-tropiques Sounder for Probing Vertical Profiles of Humidity (SAPHIR) and Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Microwave Imager (GMI) radiances.

- Assimilate Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Atmospheric Motion Vectors (AMVs) and implement log-normal wind quality control for AMVs.

- Assimilate Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite system (GOES) clear-air water vapor winds.

- Assimilate additional global navigation satellite system (GNSS) Radio Occultation (RO) observations.

- Modify pressure and hybrid coordinates transformation during the storm relocation.

- Change relocation of the vorticity and divergence fields to the relocation of u,v wind components.

- Remove bogus Tropical Storm/Hurricane data for use in Data Assimilation.

- Assimilate Global Hawk dropsonde data when available.

- Upgrade data assimilation monitoring package.

3) Changes to the post-processing

- Upgrade post-processing software to use new nemsio model output.

- Implement continuity equation to derive omega on grid space for new nems model output only.

- Modify interpolation procedure for all categorical fields including land mask, icing severity and precipitation types products to use nearest neighbor interpolation.

- Change interpolation method for In-Cloud Turbulence Potential (CTP) and CB cover (Horizontal Extent of Cumulonimbus) from 'linear' to 'nearest neighbor' to avoid averaging their own specific negative value with normal values when doing grid conversion.

Please see the NWS Service Change Notice on this upgrade for additional details.

On June 12, 2019 EMC implemented version 15 of the Global Forecast System (GFS) in production. The major component of this implementation was to replace the global spectral model with the Finite Volume Cubed Sphere (FV3) dynamical core, developed at NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL). The operational FV3GFS runs the same physics as the previous GFS, except that the Zhao-Carr microphysics with the more advanced GFDL microphysics scheme. More details on the implementation of the FV3GFS can be found in the NWS Service Change Notice, on EMC's FV3GFS page on the NOAA Virtual Lab web site, or at the "Recent GFS Implementation details" link above.

1.6 References:

Alpert, J., 2006 Sub-Grid Scale Mountain Blocking at NCEP, 20th Conf. WAF/16 Conf. NWP P2.4

Alpert, J. C., S-Y. Hong and Y-J. Kim: 1996, Sensitivity of cyclogenesis to lower troposphere enhancement of gravity wave drag using the EMC MRF, Proc. 11 Conf. On NWP, Norfolk, 322-323.

Alpert,J,, M. Kanamitsu, P. M. Caplan, J. G. Sela, G. H. White, and E. Kalnay, 1988: Mountain induced gravity wave drag parameterization in the NMC medium-range forecast model. Pre-prints, Eighth Conf. on Numerical Weather Prediction, Baltimore, MD, Amer. Meteor. Soc., 726-733.

Buehner, M., J. Morneau, and C. Charette, 2013: Four-dimensional ensemble-variational data assimilation for global deterministic weather prediction. Nonlinear Processes Geophys., 20, 669-682.

Chun, H.-Y., and J.-J. Baik, 1998: Momentum Flux by Thermally Induced Internal Gravity Waves and Its Approximation for Large-Scale Models. J. Atmos. Sci., 55, 3299-3310.

Chun, H.-Y., Song, I.-S., Baik, J.-J. and Y.-J. Kim. 2004: Impact of a Convectively Forced Gravity Wave Drag Parameterization in NCAR CCM3. J. Climate, 17, 3530-3547.

Chun, H.-Y., Song, M.-D., Kim, J.-W., and J.-J. Baik, 2001: Effects of Gravity Wave Drag Induced by Cumulus Convection on the Atmospheric General Circulation. J. Atmos. Sci., 58, 302-319.

Clough, S.A., M.W. Shephard, E.J. Mlawer, J.S. Delamere, M.J. Iacono, K.Cady-Pereira, S. Boukabara, and P.D. Brown, 2005: Atmospheric radiative transfer modeling: A summary of the AER codes, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer, 91, 233-244, doi:10.1016/ j.jqsrt.2004.05.058.J. Geophys. Res., 97, 15761-15785

Ebert, E.E., and J.A. Curry, 1992: A parameterization of ice cloud optical properties for climate models. J. Geophys. Res., 97, 3831-3836.

Fu, Q., 1996: An Accurate Parameterization of the Solar Radiative Properties of Cirrus Clouds for Climate Models. J. Climate, 9, 2058-2082.

Han, J., and H.-L. Pan, 2006: Sensitivity of hurricane intensity forecast to convective momentum transport parameterization. Mon. Wea. Rev., 134, 664-674.

Han, J., and H.-L. Pan, 2011: Revision of convection and vertical diffusion schemes in the NCEP global forecast system. Weather and Forecasting, 26, 520-533.

Han, J., M. Witek, J. Teixeira, R. Sun, H.-L. Pan, J. K. Fletcher, and C. S. Bretherton, 2016: Implementation in the NCEP GFS of a hybrid eddy-diffusivity mass-flux (EDMF) boundary layer parameterization with dissipative heating and modified stable boundary layer mixing. Weather and Forecasting, 31, 341-352.

Hou, Y., S. Moorthi and K. Campana, 2002: Parameterization of Solar Radiation Transfer in the NCEP Models, NCEP Office Note #441, pp46. [Available here]

Hu, Y.X., and K. Stamnes, 1993: An accurate parameterization of the radiative properties of water clouds suitable for use in climate models. J. Climate, 6, 728-74.

Iacono, M.J., E.J. Mlawer, S.A. Clough, and J.-J. Morcrette, 2000: Impact of an improved longwave radiation model, RRTM, on the energy budget and thermodynamic properties of the NCAR community climate model, CCM3, J. Geophys. Res., 105(D11), 14,873-14,890.2.

Johansson, Ake, 2008: Convectively Forced Gravity Wave Drag in the NCEP Global Weather and Climate Forecast Systems, SAIC/Environmental Modelling Center internal report.

Juang, H-M, et al. 2014:Regional Spectral Model workshop in memory of John Roads and Masao Kanamitsu, BAMS, A. Met. Soc, ES61-ES65.

Kim, Y.-J., and A. Arakawa (1995), Improvement of orographic gravity wave parameterization using a mesoscale gravity-wave model, J. Atmos. Sci.,52, 875-1902

Kleist, D. T., 2012: An evaluation of hybrid variational-ensemble data assimilation for the NCEP GFS , Ph.D. Thesis, Dept. of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, University of Maryland-College Park, 149 pp.

Lott, F and M. J. Miller: 1997, A new subgrid-scale orographic drag parameterization: Its formulation and testing, QJRMS, 123, pp101-127.

Mlawer, E.J., S.J. Taubman, P.D. Brown, M.J. Iacono, and S.A. Clough, 1997: Radiative transfer for inhomogeneous atmospheres: RRTM, a validated correlated-k model for the longwave. J. Geophys. Res., 102, 16663-16682.

Sela, J., 2009: The implementation of the sigma-pressure hybrid coordinate into the GFS. NCEP Office Note #461, pp25.

Sela, J., 2010: The derivation of sigmapressure hybrid coordinate semi-Lagrangian model equations for the GFS. NCEP Office Note #462 pp31.

Yang, F., 2009: On the Negative Water Vapor in the NCEP GFS: Sources and Solution. 23rd Conference on Weather Analysis and Forecasting/19th Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction, 1-5 June 2009, Omaha, NE.

Yang, F., K. Mitchell, Y. Hou, Y. Dai, X. Zeng, Z. Wang, and X. Liang, 2008: Dependence of land surface albedo on solar zenith angle: observations and model parameterizations. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology.No.11, Vol 47, 2963-2982

1.7 Older References:

- Alpert, J., 2006 Sub-Grid Scale Mountain Blocking at NCEP, 20th Conf. WAF/16 Conf. NWP P2.4

- Alpert, J. C., S-Y. Hong and Y-J. Kim: 1996, Sensitivity of cyclogenesis to lower troposphere enhancement of gravity wave drag using the EMC MRF, Proc. 11 Conf. On NWP, Norfolk, 322-323.

- Alpert,J,, M. Kanamitsu, P. M. Caplan, J. G. Sela, G. H. White, and E. Kalnay, 1988: Mountain induced gravity wave drag parameterization in the NMC medium-range forecast model. Pre-prints, Eighth Conf. on Numerical Weather Prediction, Baltimore, MD, Amer. Meteor. Soc., 726-733.

- Arakawa, A. and W. H. Shubert, 1974: Interaction of a Cumulus Ensemble with the Large-Scale Environment, Part I. J. Atmos. Sci., 31, 674-704.

- Asselin, R., 1972: Frequency filter for time integrations. Mon. Wea. Rev., 100, 487-490.

- Betts, A.K., S.-Y. Hong and H.-L. Pan, 1996: Comparison of NCEP-NCAR Reanalysis with 1987 FIFE data. Mon. Wea. Rev., 124, 1480-1498

- Briegleb, B. P., P. Minnus, V. Ramanathan, and E. Harrison, 1986: Comparison of regional clear-sky albedo inferred from satellite observations and model computations. J. Clim. and Appl. Meteo., 25, 214-226.

- Buehner, M., J. Morneau, and C. Charette, 2013: Four-dimensional ensemble-variational data assimilation for global deterministic weather prediction. Nonlinear Processes Geophys., 20, 669-682.

- Campana, K. A., Y-T Hou, K. E. Mitchell, S-K Yang, and R. Cullather, 1994: Improved diagnostic cloud parameterization in NMC's global model. Preprints of the Tenth Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction, Portland, OR, American Meteorological Society, 324-325.

- Charnock, H., 1955: Wind stress on a water surface. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 81, 639-640.

- Chen, F., K. Mitchell, J. Schaake, Y. Xue, H.-L. Pan, V. Koren, Q. Y. Duan, M. Ek, and A. Betts, 1996: Modeling of land surface evaporation by four schemes and comparison with FIFE observations. J. Geophys. Res., 101, D3, 7251-7268.

- Chou, M-D, 1990: Parameterizations for the absorption of solar radiation by O2 and CO2 with application to climate studies. J. Climate, 3, 209-217.

- Chou, M-D, 1992: A solar radiation model for use in climate studies. J. Atmos. Sci., 49, 762-772.

- Chou, M-D and K-T Lee, 1996: Parameterizations for the absorption of solar radiation by water vapor and ozone. J. Atmos. Sci., 53, 1204-1208.

- Chou, M.D., M. J. Suarez, C. H. Ho, M. M. H. Yan, and K. T. Lee, 1998: Parameterizations for cloud overlapping and shortwave single scattering properties for use in general circulation and cloud ensemble models. J. Climate, 11, 202-214.

- Chun, H.-Y., and J.-J. Baik, 1998: Momentum Flux by Thermally Induced Internal Gravity Waves and Its Approximation for Large-Scale Models. J. Atmos. Sci., 55, 3299-3310.

- Chun, H.-Y., Song, I.-S., Baik, J.-J. and Y.-J. Kim. 2004: Impact of a Convectively Forced Gravity Wave Drag Parameterization in NCAR CCM3. J. Climate, 17, 3530-3547.

- Chun, H.-Y., Song, M.-D., Kim, J.-W., and J.-J. Baik, 2001: Effects of Gravity Wave Drag Induced by Cumulus Convection on the Atmospheric General Circulation. J. Atmos. Sci., 58, 302-319.

- Clough, S.A., M.J. Iacono, and J.-L. Moncet, 1992: Line-by-line calculations of atmospheric fluxes and cooling rates: Application to water vapor. J. Geophys. Res., 97, 15761-15785.

- Clough, S.A., M.W. Shephard, E.J. Mlawer, J.S. Delamere, M.J. Iacono, K.Cady-Pereira, S. Boukabara, and P.D. Brown, 2005: Atmospheric radiative transfer modeling: A summary of the AER codes, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer, 91, 233-244, doi:10.1016/ j.jqsrt.2004.05.058.J. Geophys. Res., 97, 15761-15785

- Coakley, J. A., R. D. Cess, and F. B. Yurevich, 1983: The effect of tropospheric aerosols on the earth's radiation budget: a parameterization for climate models. J. Atmos. Sci., 42, 1408-1429.

- Dorman, J.L., and P.J. Sellers, 1989: A global climatology of albedo, roughness length and stomatal resistance for atmospheric general circulation models as represented by the Simple Biosphere model (SiB). J. Appl. Meteor., 28, 833-855.

- Ebert, E.E., and J.A. Curry, 1992: A parameterization of ice cloud optical properties for climate models. J. Geophys. Res., 97, 3831-3836.

- Environmental Modeling Center, 2003: The GFS Atmospheric Model. NCEP Office Note 442, Global Climate and Weather Modeling Branch, EMC, Camp Springs, Maryland.

- Fanglin Yang, Kenneth Mitchell, Yu-Tai Hou, Yongjiu Dai, Xubin Zeng, Zhou Wang, and Xin-Zhong Liang, 2008: Dependence of land surface albedo on solar zenith angle: observations and model parameterizations. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. No.11, Vol 47, 2963-2982.

- Fanglin Yang, Hua-Lu Pan, Steve Krueger, Shrinivas Moorthi, Stephen Lord, 2006: Evaluation of the NCEP Global Forecast System at the ARM SGP Site. Monthly Weather Review. 134, No. 12, 3668-3690.

- Frohlich, C. and G. E. Shaw, 1980: New determination of Rayleigh scattering in the terrestrial atmosphere. Appl. Opt., 14, 1773-1775.

- Fu, Q., 1996: An Accurate Parameterization of the Solar Radiative Properties of Cirrus Clouds for Climate Models. J. Climate, 9, 2058-2082.

- Hess, M., P. Koepke, and I. Schult, 1998: Optical properties of aerosols and clouds: The software package OPAC. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc., 79, 831-844.

- Grell, G. A., 1993: Prognostic Evaluation of Assumprions Used by Cumulus Parameterizations. Mon. Wea. Rev., 121, 764-787.

- Grumbine, R. W., 1994: A sea-ice albedo experiment with the NMC medium range forecast model. Weather and Forecasting, 9, 453-456.

- Han, J., and H.-L. Pan, 2006: Sensitivity of hurricane intensity forecast to convective momentum transport parameterization. Mon. Wea. Rev., 134, 664-674.

- Han, J., and H.-L. Pan, 2011: Revision of convection and vertical diffusion schemes in the NCEP global forecast system. Weather and Forecasting, 26, 520-533.

- Han, J., M. Witek, J. Teixeira, R. Sun, H.-L. Pan, J. K. Fletcher, and C. S. Bretherton, 2016: Implementation in the NCEP GFS of a hybrid eddy-diffusivity mass-flux (EDMF) boundary layer parameterization with dissipative heating and modified stable boundary layer mixing. Weather and Forecasting, 31, 341-352.

- Hong, S.-Y. and H.-L. Pan, 1996: Nonlocal boundary layer vertical diffusion in a medium-range forecast model. Mon. Wea. Rev., 124, 2322-2339.

- Hong, S.-Y., 1999: New global orography data sets. NCEP Office Note #424.

- Hou, Y-T, K. A. Campana and S-K Yang, 1996: Shortwave radiation calculations in the NCEP's global model. International Radiation Symposium, IRS-96, August 19-24, Fairbanks, AL.

- Hou, Y.-T., S. Moorthi, and K.A. Campana, 2002: Parameterization of solar radiation transfer in the NCEP models. NCEP Office Note 441.

- Hu, Y.X., and K. Stamnes, 1993: An accurate parameterization of the radiative properties of water clouds suitable for use in climate models. J. Climate, 6, 728-742.

- Iacono, M.J., E.J. Mlawer, S.A. Clough, and J.-J. Morcrette, 2000: Impact of an improved longwave radiation model, RRTM, on the energy budget and thermodynamic properties of the NCAR community climate model, CCM3, J. Geophys. Res., 105(D11), 14,873-14,890.2.

- Johansson, Ake, 2008: Convectively Forced Gravity Wave Drag in the NCEP Global Weather and Climate Forecast Systems, SAIC/Environmental Modelling Center internal report.

- Joseph, D., 1980: Navy 10' global elevation values. National Center for Atmospheric Research notes on the FNWC terrain data set, 3 pp.

- Juang, H.-M. H., and M. Kanamitsu, 2001: The computational performance of the NCEP seasonal forecast model on Fujitsu VPP5000 at ECMWF. Proc. Ninth ECMWF Workshop on the use of high performance computing in Meteorology, Reading, UK, ECMWF, 338-347.

- Juang, H.-M. H., 2004: A reduced spectral transform for the NCEP seasonal Forecast Global Spectral Atmospheric Model. Monthly Weather Review, 132, 1019-1035.

- Juang, H.-M. H., 2005: Discrete generalized hybrid vertical coordinates by a mass, energy, and angular momentum conserving finite-difference scheme. NCEP Office Note 455, 35pp.

- Juang, H.-M. H., and S.-Y. Hong, 2010: Forward semi-Lagrangian advection with mass conservation and positive definiteness for falling hydrometeors. Monthly Weather Review, 138, 1778-1791.

- Juang, H.-M. H., 2011:A multiconserving discretization with enthalpy as a thermodynamic prognostic variable in generalized hybrid vertical coordinates for the NCEP global forecast system. Monthly Weather Review, 139, 1583-1607.

- Juang, H-M, et al. 2014:Regional Spectral Model workshop in memory of John Roads and Masao Kanamitsu, BAMS, A. Met. Soc, ES61-ES65.

- Juang, H.-M. H., 2014: A discretization of deep-atmospheric nonhydrostatic dynamics on generalized hybrid vertical coordinates for NCEP global spectral model. NCEP Office Note 477, 40pp.

- Kalnay, E. and M. Kanamitsu, 1988: Time Scheme for Stronglyt Nonlinear Damping Equations. Mon. Wea. Rev., 116, 1945-1958.

- Kalnay, M. Kanamitsu, and W.E. Baker, 1990: Global numerical weather prediction at the National Meteorological Center. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 71, 1410-1428.

- Kanamitsu, M., 1989: Description of the NMC global data assimilation and forecast system. Wea. and Forecasting, 4, 335-342.

- Kanamitsu, M., J.C. Alpert, K.A. Campana, P.M. Caplan, D.G. Deaven, M. Iredell, B. Katz, H.-L. Pan, J. Sela, and G.H. White, 1991: Recent changes implemented into the global forecast system at NMC. Wea. and Forecasting, 6, 425-435.

- Kiehl, J.T., J. J. Hack, G. B. Bonan, B. A. Boville, D. L. Williamson, and P. J. Rasch, 1998: The national center for atmospheric research community climate model CCM3. J. Climate, 11,1131-1149.

- Kim, Y-J and A. Arakawa, 1995: Improvement of orographic gravity wave parameterization using a mesoscale gravity wave model. J. Atmos. Sci. 52, 11, 1875-1902.

- Kleist, D.T., D.F. Parrish, J.C. Derber, R. Treadon, R.M. Errico, and R. Yang, 2008: Improving incremental balance in the GSI 3DVAR analysis system. Mon. Wea. Rev., 137, 1046-1060.

- Kleist, D.T., D.F. Parrish, J.C. Derber, R. Treadon, W.-S. Wu, and S. Lord, 2008: Implementation of a new 3DVAR analysis as part of the NCEP global data assimilation system. Wea. Forecasting., 24, 1691-1705.

- Kleist, D. T., 2012: An evaluation of hybrid variational-ensemble data assimilation for the NCEP GFS , Ph.D. Thesis, Dept. of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, University of Maryland-College Park, 149 pp.

- Koepke, P., M. Hess, I. Schult, and E.P. Shettle, 1997: Global aerosol data set. MPI Meteorologie Hamburg Report No. 243, 44 pp.

- Lacis, A.A., and J. E. Hansen, 1974: A parameterization for the absorption of solar radiation in the Earth's atmosphere. J. Atmos. Sci., 31, 118-133.

- Leith, C.E., 1971: Atmospheric predictability and two-dimensional turbulence. J. Atmos. Sci., 28, 145-161.

- Lindzen, R.S., 1981: Turbulence and stress due to gravity wave and tidal breakdown. J. Geophys. Res., 86, 9707-9714.

- Lott, F and M. J. Miller: 1997, A new subgrid-scale orographic drag parameterization: Its formulation and testing, QJRMS, 123, pp101-127.

- Matthews, E., 1985: "Atlas of Archived Vegetation, Land Use, and Seasonal Albedo Data Sets.", NASA Technical Memorandum 86199, Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York.

- Mitchell, K. E. and D. C. Hahn, 1989: Development of a cloud forecast scheme for the GL baseline global spectral model. GL-TR-89-0343, Geophysics Laboratory, Hanscom AFB, MA.

- Mlawer, E.J., S.J. Taubman, P.D. Brown, M.J. Iacono, and S.A. Clough, 1997: Radiative transfer for inhomogeneous atmospheres: RRTM, a validated correlated-k model for the longwave. J. Geophys. Res., 102, 16663-16682.

- Miyakoda, K., and J. Sirutis, 1986: Manual of the E-physics. [Available from Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, Princeton University, P.O. Box 308, Princeton, NJ 08542.]

- NMC Development Division, 1988: Documentation of the research version of the NMC Medium-Range Forecasting Model. NMC Development Division, Camp Springs, MD, 504 pp.

- Pan, H-L. and L. Mahrt, 1987: Interaction between soil hydrology and boundary layer developments. Boundary Layer Meteor., 38, 185-202.

- Pan, H.-L. and W.-S. Wu, 1995: Implementing a Mass Flux Convection Parameterization Package for the NMC Medium-Range Forecast Model. NMC Office Note, No. 409, 40pp. [ Available from NCEP, 5200 Auth Road, Washington, DC 20233 ]

- Pierrehumbert, R.T., 1987: An essay on the parameterization of orographic wave drag. Observation, Theory, and Modelling of Orographic Effects, Vol. 1, Dec. 1986, European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts, Reading, UK, 251-282.

- Ramsay, B.H., 1998: The interactive multisensor snow and ice mapping system. Hydrol. Process. 12, 1537-1546.

- Reynolds, R. W. and T. M. Smith, 1994: Improved global sea surface temperature analyses. J. Climate, 7, 929-948.

- Roberts, R.E., J.A. Selby, and L.M. Biberman, 1976: Infrared continuum absorption by atmospheric water vapor in the 8-12 micron window. Appl. Optics., 15, 2085-2090.

- Rodgers, C.D., 1968: Some extension and applications of the new random model for molecular band transmission. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 94, 99-102.

- Schwarzkopf, M.D., and S.B. Fels, 1985: Improvements to the algorithm for computing CO2 transmissivities and cooling rates. J. Geophys. Res., 90, 10541-10550.

- Schwarzkopf, M.D., and S.B. Fels, 1991: The simplified exchange method revisited: An accurate, rapid method for computation of infrared cooling rates and fluxes. J. Geophys. Res., 96, 9075-9096.

- Sela, J., 1980: Spectral modeling at the National Meteorological Center, Mon. Wea. Rev., 108, 1279-1292.

- Sela, J., 2009: The implementation of the sigma-pressure hybrid coordinate into the GFS. NCEP Office Note #461, pp25.

- Sela, J., 2010: The derivation of sigmapressure hybrid coordinate semi-Lagrangian model equations for the GFS. NCEP Office Note #462 pp31.

- Slingo, A., 1989: A GCM parameterization for the shortwave radiative properties pf water clouds. J. Atmos. Sci.,46, 1419-1427.

- Slingo, J.M., 1987: The development and verification of a cloud prediction model for the ECMWF model. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 113, 899-927.

- Slingo, A., 1989: A GCM parameterization for the shortwave radiative properties pf water clouds. J. Atmos. Sci.,46, 1419-1427.

- Stephens, G. L., 1984: The parameterization of radiation for numerical weather prediction and climate models. Mon. Wea. Rew., 112, 826-867.

- Staylor, W. F. and A. C. Wilbur, 1990: Global surface albedoes estimated from ERBE data. Preprints of the Seventh Conference on Atmospheric Radiation, San Francisco CA, American Meteorological Society, 231-236.

- Sundqvist, H., E. Berge, and J. E. Kristjansson, 1989: Condensation and cloud studies with mesoscale numerical weather prediction model. Mon. Wea. Rev., 117, 1641- 1757.

- Tiedtke, M., 1983: The sensitivity of the time-mean large-scale flow to cumulus convection in the ECMWF model. ECMWF Workshop on Convection in Large-Scale Models, 28 November-1 December 1983, Reading, England, pp. 297-316.

- Troen, I. and L. Mahrt, 1986: A simple model of the atmospheric boundary layer; Sensitivity to surface evaporation. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 37, 129-148

- Xu, K. M., and D. A. Randall, 1996: A semiempirical cloudiness parameterization for use in climate models. J. Atmos. Sci., 53, 3084-3102.

- Yang, F., 2009: On the Negative Water Vapor in the NCEP GFS: Sources and Solution. 23rd Conference on Weather Analysis and Forecasting/19th Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction, 1-5 June 2009, Omaha, NE.

- Yang, F., K. Mitchell, Y. Hou, Y. Dai, X. Zeng, Z. Wang, and X. Liang, 2008: Dependence of land surface albedo on solar zenith angle: observations and model parameterizations. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology.No.11, Vol 47, 2963-2982

- Zeng, X., M. Zhao, and R.E. Dickinson, 1998: Intercomparison of bulk aerodynamical algorithms for the computation of sea surface fluxes using TOGA COARE and TAO data. J. Climate, 11, 2628-2644.

- Zhao, Q. Y., and F. H. Carr, 1997: A prognostic cloud scheme for operational NWP models. Mon. Wea. Rev., 125,1931-1953.

- Zheng, W., H. Wei, Z. Wang, X. Zeng, J. Meng, M. Ek, K. Mitchell, and J. Derber, 2012: Improvement of daytime land surface skin temperature over arid regions in the NCEP GFS model and its impact on satellite data assimilation. J. Geophys. Res., 117, D06117, doi:10.1029/2011JD015901.